How do we interpret our Quantum Reality? With Cats?

There are many interpretations to quantum mechanics, some more popular than others. Let's take a look at what they propose.

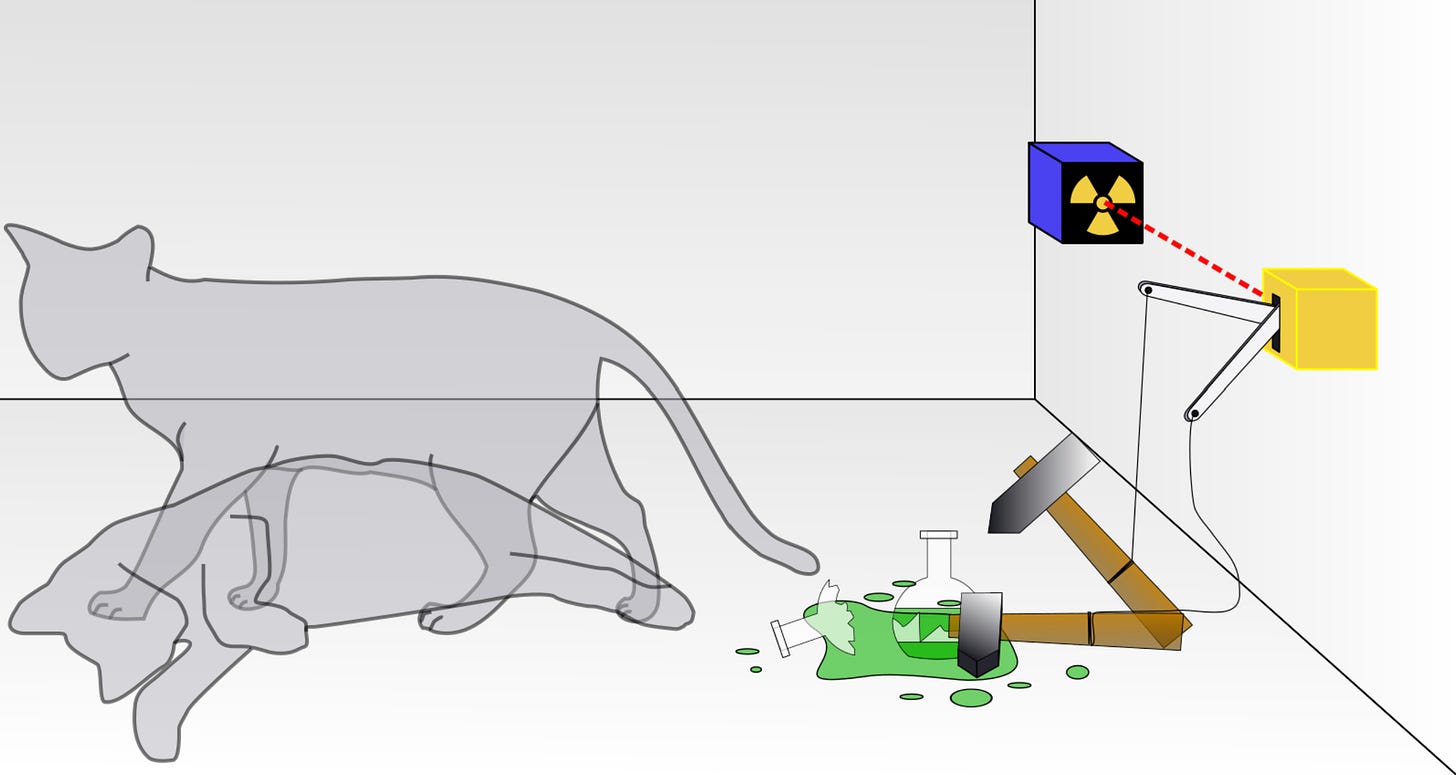

Quantum mechanics is an incredible theory of reality, based on the smallest interactions in the universe. It was first introduced by physicist Max Planck in 1900 (who showed that energy is quantised) and was made comprehensive by Erwin Schrödinger (who developed the description of a quantum system’s evolution in time). Admittedly, Schrödinger is better known for his famous cat analogy, which describes a state of superposition.

There are, of course, many other famous physicists to mention who have contributed greatly to the development of quantum theory. Although it would be remiss not to outline their work, we will only be able to look at a few within this article.

Throughout schools and universities, quantum mechanics is generally taught the same way. Through almost a century of trials and testing, quantum mechanics has held up against precise and rigorous experiments (in both the physical and thought sense of the word experiment). But there lies a fundamental issue. Even though the maths and physics works - what do the answers actually mean for our reality? For example, are the results of quantum mechanics even real? What minimum amount of observation is required for measurement? Is quantum mechanics deterministic, stochastic, local or non-local? In most textbooks, for example, the Copenhagen Interpretation is taught - which may be considered the most popular way of interpreting our quantum reality. Although a century of debate has yielded no consensus among philosophers and physicists, let us muse over some of top interpretations.

The Copenhagen Interpretation

One of the oldest, and certainly the most commonly taught interpretation, is known as the Copenhagen Interpretation, attributed to Niels Bohr and Werner Heisenberg and first appearing in 1920. It essentially rests upon the principle that quantum mechanics is intrinsically indeterministic. For example, a quantum particle in superposition does not exist in one particular state or another, but in a separate state that represents all possible states at once. It is only when we go to observe said particle that it is forced to become a definite state - but this is a probabilistic process. For example, Schrödinger’s cat may be forced into the state of being alive or the state of death upon observation, with the specific probability characterising the superposition in the first place. We call this process ‘Wavefunction Collapse’. Here wavefunction refers to the entire state of a quantum particle or system; collapsing the wavefunction means that we force it to take on a definite property rather than to stay in superposition. Funnily enough, it is said that Heisenberg and Bohr disagreed over what the actual ‘observer’ is within this framework. In their defence, this might be one of the hardest things to conceptualise in quantum mechanics.

Another interesting thing to emerge from the Copenhagen Interpretation is the Principle of Complementarity. This foundational idea encompasses two main things:

The Uncertainty Principle: Certain pairs of physical properties cannot be simultaneously ascertained with 100% precision. For example, you cannot learn with certainty both the momentum and the position of any particle at the same time. In other words, the more accurately you measure the momentum, the less accurately you can measure the position.

Wave-particle duality: Fundamental particles, such as photons or electrons, can exhibit both particle and wave-like properties. This contradiction, which can be experimentally verified quite easily, portrays the limitations of classical theories in describing quantum objects.

The Many Worlds Interpretation

This is one of my favourite interpretations. American physicist Hugh Everett introduced this idea in 1955, whilst being a PhD student at Princeton. His original analogy was that idea that when a cell splits into two daughter cells, each would be identical up until the point of splitting and would then have separate memories following this. Now let’s see how this translates to the quantum side. The most important part of this interpretation is that there is no wavefunction collapse when an observer measures the quantum state. Instead, there is a universal wavefunction and all possible outcomes of a quantum measurement are physically realised in different universes. For example, in the case of Schrödinger’s cat, the ‘alive’ cat and the ‘dead’ cat are in different branches of the multiverse - both exist but cannot interact with each other as they are in different universes.

“Everett did point out that since no observer would ever be aware of the existence of the other worlds, to claim that they cannot be there because we cannot see them is no more valid than claiming that the Earth cannot be orbiting around the Sun because we cannot feel the movement.”

With help from David Deutsch, British physicist from the University of Oxford and known as ‘the father of quantum computing’, we can take this concept of many-universes further. A normal classical computer works on the basis of tiny switches which can either be in state 1 or 0. A quantum computer, on the other hand, can place the switches into superpositions - allowing for states which are both 0 and 1. Properties such as this can allow for exponentially faster and more powerful computing. Deutsch therefore cleverly argues that quantum computer calculations are actually being carried out on identical computers within different parallel universes. The number of parallel quantum computers is equivalent to the number of possible states within the superposition.

You may or may not choose to believe this. It can have some wild implications. For example, a quantum computer with over 300 qubits (which easily exists now) would generate more parallel universes than there are atoms in the known universe.

QBism (Quantum Bayesianism)

This is quite a radical interpretation, emphasising the role of the observer and of human involvement. Classical physics tries to push the narrative that the universe is made of laws that would apply regardless of whether conscious humans exist or not. QBism is quite different. According to QBism, the result that outputs from a measurement on a quantum state is merely the observer updating their beliefs after making a measurement - I suppose passively in a sense. Even entanglement over huge distances is explained using the same logic. QBism treats the wavefunction of a quantum system as the single observer’s subjective knowledge, meaning that one observer cannot affect the observation of another observer.

Personally, I think it’s a theory that is unlikely to have much practical significance. It raises lots of questions, such as does the observer have to be a human, could it instead be a dog or perhaps a flower? How small should the observer have to be and why can’t subjective observations mess with each other? If quantum mechanics only describes the subjective observers reality, which observer does it describe?

If you ask me, these questions will be pondered forever.

Concluding thoughts

There are so many fascinating interpretations of quantum mechanics, and I’ve only been able to scratch the surface on them. I should like to write more about them, so stay posted for another article in the future. As far as quantum computing is concerned, the interpretation of quantum mechanics doesn’t matter so much. The field of quantum computing is more about getting results from inherently quantum systems, and thus being able to surpass classical computing approaches. However, in order to design novel quantum computing setups and algorithms, out-of-the-box perspectives to quantum mechanics may be necessary. Therefore, it is never quite right to completely dismiss a school of thought when it comes to quantum mechanics.

Very interesting as usual. Alot to take in this time. To get a complete grasp I’ve read the article as Part1 and Part2.